We confuse two kinds of hard work a little more than what should be an innocuous ignorance. Hard work as an imposition vs a side effect. On the surface, they both look similar. After all they both convey a certain level of discomforting intensity to the watcher. Add to it the misguided opinions implying more or less effort necessarily means better output and the situation becomes a heavy mess. Part of the misunderstanding comes from misreadings of the intentions that go before applied effort. Rest from what comes after, in the form of observed productivity. Both of these wrongly frame effort as the central dogma driving productivity.

Like any other contentious topic, you can create reasonable arguments for any side by cherry picking. In the case of making hard work a central force, stories of achievers work well. And these are then accepted by us without much resistance since we look for actionables without getting involved in the process of developing them. While it is not different from other popular misunderstandings, there are deeper issues concerning the mental and physical effects of adages flowering under it.

In this post, I will try to lay down why I feel our current way of observing raw effort spent, a.k.a. hard work, is at best immature and at worst a gross misunderstanding of the process of creating something truly meaningful.

There are no new ideas here. Just a series of observations and thoughts.

1. Observance

Some time back I read Daily Rituals: How Artists Work 1 which documents routines of famous artists and creators. Even though the work merely catalogues schedules and is not meant to be prescriptive, I will cherry pick a few pieces that have potential to circulate around as bits of you-should-do-this wisdom.

At the very first level, and arguably the most common, we have the spend-20-hours-a-day working style:

…he only needed three hours of sleep. He’d get up early and write letters, mathematical letters. He’d sleep downstairs. The first time he stayed, the clock was set wrong. It said 7:00, but it was really 4:30 A.M. He thought we should be up working, so he turned on the TV full blast. Later, when he knew me better, he’d come up at some early hour and tap on the bedroom door. “Ralph, do you exist?” The pace was grueling. He’d want to work from 8:00 A.M. until 1:30 A.M. Sure we’d break for short meals but we’d write on napkins and talk math the whole time. He’d stay a week or two and you’d collapse at the end.

Then a little rarer, but still misused are bits where we hint at understanding hard work as a side effect:

I work every day. I work weekends, I work nights.… [S]ome people looking at that from the outside might use that modern term “workaholic,” or might see this as obsessive or destructive. But it’s not work to me, it’s just what I do, that’s my life

A little less hours:

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you stop you are as empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing can hurt you, nothing can happen, nothing means anything until the next day when you do it again. It is the wait until that next day that is hard to get through.

Lesser even:

The first, and best, of his work periods began at 8:00 A.M., after Darwin had taken a short walk and had a solitary breakfast. Following ninety minutes of focused work in his study—disrupted only by occasional trips to the snuff jar that he kept on a table in the hallway—Darwin met his wife, Emma, in the drawing room to receive the day’s post…

At 10:30 Darwin returned to his study and did more work until noon or a quarter after. He considered this the end of his workday, and would often remark in a satisfied voice, “I’ve done a good day’s work.”…

He came back downstairs at 4:00 to embark on his third walk of the day, which lasted for half an hour, and then returned to his study for another hour of work, tying up any loose ends from earlier in the day…

After two games of backgammon, he would read a scientific book and, just before bed, lie on the sofa and listen to Emma play the piano. He left the drawing room at about 10:00 and was in bed within a half-hour, although he generally had trouble getting to sleep and would often lie awake for hours, his mind working at some problem that he had failed to solve during the day.

Hopefully, just counting working hours as something meaningful looks too shallow. You can still argue about a few things but nothing as conclusive as this title → You Should Work Less Hours—Darwin Did. Our obsession with exact answers to the question What should I do? makes most of the metric focused analyses of productivity vulnerable to dramatic misinterpretations. While the article does more in-depth analysis that its title suggests, the popular takeaway will still be about lesser hours. Similarly, I can find supportive content for any of the quoted texts and come out reasonably convinced that I now know the way everyone should work.

Hours spent is an intermediate cause and effect in the chain of creation, not a primary one. Most of the justifications of this being the primary force are superficial. Reading a log of achievements backward and stopping early misses out so much in terms of context as to basically become a cargo cult.

2. Intentions

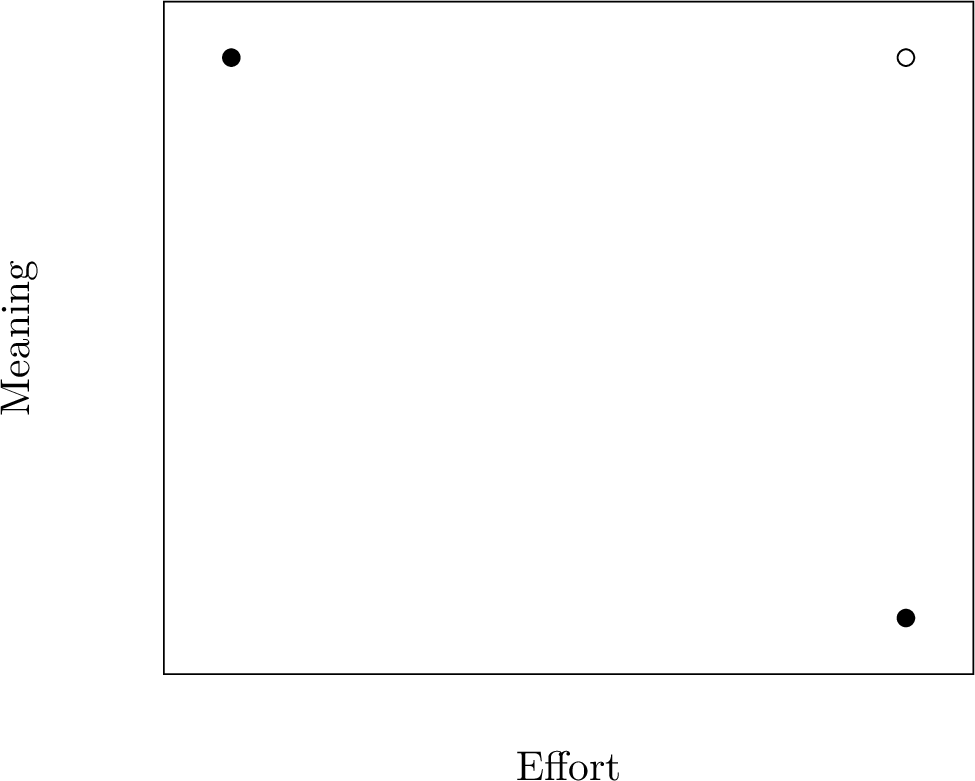

Other than observing yield, reading input intentions behind effort is also a piece which we err in. Intent behind effort can be put on a rough scale of direct personal meaning involved in the act. Here is a qualitative effort vs meaning plot:

The uninteresting (and healthy) case is when you dedicate effort on something meaningful, the top right of the plot2.

More interesting are the following two cases and the trajectory they take to go to top right:

- Top left. You have meaning but not proportionately enough effort.

- Bottom right. You are putting in effort without meaning.

In first, the effort comes after the meaning. To get to the healthy zone you tend to pull in discipline, either on your own or using various forms of guidance. The aim for putting in effort is clearly for self improvement, something you are closely connected to. Even the more rigorous effort tracking attempts don't hurt here.

He tracked his daily word output on a chart—“so as not to kid myself,” he said.

In the second, you try to move up by constructing a sort of meaning using a borrowed vocabulary. This is mostly due to certain direct imposition of absolute effort values. Some of these can be good and are important in the early training process for a person, under proper mentoring. But most are just one-size-fits-all rules applied after seeing success with similar mechanism elsewhere.

These two trajectories have wildly different impacts even though they might show similar yields in short term and confirm our faulty intuitions about effort.

3. Effects at large

Even the most extreme productivity and effort related moves do little or no harm at personal level3. You try little of this and that, then you replace whatever didn't work. This works well for things in your control but there always will be things that are not in your control. Specially in partial meritocratic 4 structures in which most of us find ourselves, where people affecting you don't have complete understanding of various aspects of your work style.

Because we think effort directly relates to yield and don't try to differentiate the backing intentions, we end up directly imposing hard work wherever possible. Many of the cases of work related stress and dissatisfaction can be mapped to such meaningless imposition of effort. The impacts range from suboptimal creative output to deeper, long term and more indirect personal and societal issues.

I recently saw this Github repository → 996.ICU supporting a case against unusually long working hours in China. While this is an extreme example, you can find many similar but milder cases which don't respect the personal dynamics of effort. All of them have the following more fundamental problems:

- organizational disconnects leading to disproportionately less meaning in work compared to effort

- immature/wrong management imposing disproportionately high effort

- wrong people in wrong jobs5

Fetishism with imposed working hours and community counterattacks is not a new thing and has decent history going back, at least, to the industrial revolution. From what I understand, few of these are intentional and justify themselves by putting various kinds of work on a creativity spectrum. These can be read as being fantastically practical or cruelly discriminative. I am not knowledgeable enough to choose sides here. I am also not worried about these few, but about the rest who follow without having built an original and situated ideology about work themselves. By definition, the rest cover and impact a major segment of real world populace, a segment where the popular definitions of work, life, etc. are forged. And it's in the popular definitions that subtle confusions cause the most trouble.

I concede that thinking in terms of above points might sound borderline utopian. It might be too late to avoid talking about hours at all and achieve a sort of global work renaissance now. But amidst all the practical arguments and counterarguments, we also need to question our stances on the fundamental points which define what is and should be the meaning of work itself.

Of course you need to put effort to produce things, but it's not what primarily produces great outcomes. Hours spent is something that takes care of itself in the chain of creation and needs no independent push. This means that talking about and promoting formulations of effort is meaningless unless they are consumed in an experimental setting aimed to improve personal workflows.

What does produce great outcomes though? I don't know. Not at the moment. But this uncertainty is still meaningful, specially when dealing with other people in a team like environment. Not respecting this creates an environment of unhealthy machismo surrounding the amount of hours spent which is really hard to break out from.

Talking about teams, organizational work these days have another dimension of competitiveness which inflates short term gains. Lazy solutions like putting more effort, along with general snowballing across attrition and renewals ends up showing decent results with a direct causal connection which makes us even more lazier. But we need to do better.

Getting good output from a team in a competitive setting preserving meaning is a hard problem. Harder than most of the technically hard problems. This needs time spent in careful thinking and deliberations within specific contexts the people are in. In positions of control and influence6, probably the most important responsibility for us is to not let ready made answers like 'spend more hours' go through ourselves untouched and unturned.

Footnotes:

The quotes in this post are all from this book unless stated otherwise.

Note that the absolute magnitudes are not important at all.

Or at least don't do anything you personally didn't plan for.

In the partial function sense.

This, admittedly, is just a culmination of top two but should be seen to also cover fault in people vs only in the organizations.

Which is getting increasingly common in tech scene, without people realizing it.